Guest Fest: Zachary Jernigan Discusses How Race Frames his Science Fiction and Fantasy Writing

Share

First off: Thank you, Alicia, for asking me to write a guest post. I'm encouraged by your enthusiastic response to the recent interview on the subject of Writing About Race in Science Fiction and Fantasy I conducted with authors David Anthony Durham, Aliette de Bodard, Adrian Tchaikovsky, and Ken Liu. I'm also humbled that you'd enquire about my own work.

I thought of several ways to approach this post. I was asked to comment on how race frames my writing, and I don't want to flub it up. But, honestly, as I sat and considered all the things I wanted to say, I became more and more worried that I'd just overcomplicate things in an effort to make it all gel. Thus, I've trashed the idea of writing a cohesive essay and simply decided to make a chronological list of the experiences that have informed—and continue to inform—my interest in the subject of race in sff literature. Hopefully, it won't seem incoherent.

1. Growing up, I was often discouraged by books that featured non-white protagonists. For years, the reason behind this evaded me. Of course, it's easy to say that young Zack wanted to place himself in the lead character's role, that he had a hard time envisioning himself as anything other than a white boy—and sure, that makes sense, but it also misses the mark: this rationale neglects the way racism informed my reading preferences.

It's safe to say that as a child I sided with a majority of other white folks who looked down upon people of color. I took in what my teachers told me, what my parents told me, what TV told me. I listened to good, honest people say things that even they would deny having said or thought.

And then, just as unthinkingly, I regurgitated it.

This and other understandings—that racism can be sustained by largely well-intentioned people (such as my parents) precisely because they do not question what they've always been told; that racism grows best in the hearts of woman and men who segregate themselves from people of different ethnicities—have allowed me to grow. They have opened the world to me in ways I couldn't have imagined as a child or young adult.

2. I was maybe 19 or 20 the first time a black woman flirted with me (in an obvious enough way that I realized I was being flirted with). I recall being thrilled in a singular way—a way I'd never experienced before. I remember feeling accepted, not just as a man, but as a human being. Not just a white guy, suitable only for white women.

It's sad to say, but before that moment I'd never really considered the possibility that I might date a black woman, that I might kiss a black woman. Before that moment, I saw walls between people—walls that kept me from seeing the beauty in other individuals; walls that served only to keep me boxed into a certain world, good friend and companion to only a certain kind of person.

It hurts thinking about how ignorant, how blind, a young man can be. But it also makes me smile to know how fundamentally an experience, no matter how trivial it may seem to others, can change him.

3. By the age of twenty-five, I was a well read guy—in science fiction and fantasy as well as "literary" fiction. I thought of myself as an inclusive reader, yet if I'm to be completely honest with myself I have to admit that I still hadn't embraced non-white characters. Sure, I would read a book with a POC protagonist, but I wouldn't invest as much of myself in it.

Wow, that sounds terrible.

And it is, but I think it's also a very common thing for white people—at least in the United States. Everywhere we (white people) look in the media, there are more white people. Lord, if you just watched TV and movies, you'd think the country was 90% white. I'm not telling you anything new, of course, and I'm not defending myself or anyone else who takes it all in and never questions.

But I am hoping you understand why it might be that white folks have a difficult time placing themselves in other people's shoes.

For most of us, the default setting of all people is white.

Whatever. I can talk all day about why it's difficult to be so abnormally advantaged by the sheer dumb luck of being born white, but I wouldn't even be convincing myself. Compared to most people, my life hasn't been difficult at all—at least not materially. My parents weren't rich, but they were well above the poverty line. I inherited good genes, grew up tall because I was well fed. I was educated well.

Wait. Let me linger on that last one.

Educated well?

Is it possible to argue that my education was anywhere near sufficient if I couldn't sympathize with other people just because they were sheathed in different shades of skin?

4. For the latter half my twenty-fifth year, I lived in Santiago, Chile. I realized that despite the fact that my skin was about the same color as most of the people in the city, a Chilean could spot me from a mile away. I didn't even have to say anything; they saw it in my walk, in my bearing, in the lines of my face.

5. A year later, I was living in Portland, Oregon. I worked just down the street at Powell's Books.

One day, a remarkable thing occurred at the book buyers' counter.

A man came in to sell his books, and immediately pegged one of the employees with a stare—intensely, as if his eyes were laser-guided. Seeing this, the woman who was evaluating the customer's books asked if he knew the employee.

"No," the man said, "but he's a Croat. They're less than human."

Later, the male employee said that he had recognized the man as Serbian immediately.

Here were two men who looked, to most of us, like members of the same race. Yet neither of them would mistake the other in a million years.

6. Because of #4 and #5, I came to realize that the issue of race (and ethnicity) is far more complicated than any one person can truly comprehend. This realization, ironically, is a cause for sorrow as well as joy.

7. By my late twenties, I'd internalized some of the lessons about race other people were kind, patient, or simply present enough to impart to me. I'd also begun writing stories, and to my delight I found myself enthusiastically attempting to portray the kinds of characters I'd previously read with less than full enthusiasm. I did this with no little fear, of course; I didn't want to get anything wrong. I didn't want to steal, or misrepresent. I wanted people to see that I was trying—no, not to make a point about how great this white dude can be (Oh, how open-minded of him!), but to communicate my newfound enthusiasm for portraying folks whose skin tones (and genders, and sexual orientations, and religions...) were different than mine.

In those early stages of writing, I'm afraid this enthusiasm got the best of me. I made exotic the kinds of things that were normal to the people I was writing about. It took me some time to realize that someone's race—and his or her attendant culture—is both remarkable and entirely ordinary, but always worth celebrating.

I think one's job as a writer is to do justice to one's characters. Their upbringings, whether or not they hail from Earth. Their unique and commonplace beauty. If you don't know something about a certain race (ideology, technology, etc.), it's best not to make it up. You'll get called out, look like a fool, and possibly do some damage. Build on what you know, and remain silent about what you don't.

Or, even better, educate yourself.

After all, it's not a writer's job to appropriate someone else's identity and redefine it according to his or her ignorance. That's called lying, and despite the fact that fiction is made up, it shouldn't be a lie.

Science fiction and fantasy offer readers and writers a unique opportunity: To see things they wouldn't ever see in the ordinary world, to transport them to places alien and magical. We can imagine any scenario and make it work. We are not bound by the rules.

While this makes startling feats of worldbuilding possible, it's best to remind ourselves now and then that the greatest vistas are not of mountains or streams or valleys (or stars), but of each other—the whole mass of us people (and this includes our animal companions and our alien/magical neighbors), all slogging forward together. As the field of speculative literature grows, so must our awareness of the potential in everyone around us.

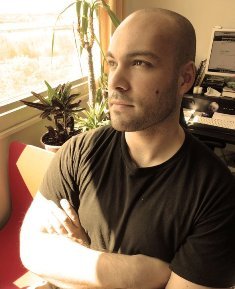

Zachary Jernigan is a Spectrum Award-shortlisted science fiction and fantasy author living in Arizona. zacharyjernigan.blogspot.com